Acoustic guitars seem so charming and sophisticated. They are the perfect shimmery chameleons to class up and emotionalize a wide range of songs, articulating love, regret, loss, joy and other aspects of the human condition. But that classy and oh-so-refined temperament is a ruse, and the truth can terrorize your mix session.

Because, in reality, acoustic guitars are feral demons.

An acoustic guitar’s raging overtones, surging bass, sparkling midrange and glistening treble can overwhelm the frequency spectrum of an entire track and threaten to obstruct every other element in the mix. If left to rampage unchecked, an acoustic guitar’s sonic onslaught can coerce your poor song into sounding boomy, muddy, piercing, strident and generally unpleasant to listen to.

Fortunately, you have a superpower at your disposal to bend and shape an acoustic guitar’s aural assault into exactly what you want it to sound like. It’s called parametric EQ.

Current parametric EQ plug-ins give you and your DAW of choice near-ultimate control over a track’s frequency range. Used adroitly, EQ can transform even the most problematic, out-of-control mix into a final product of spectral beauty and impact.

So, here’s some EQ education to help you refine the sound of any acoustic guitar model sitting in every mix you undertake. To get you there, we’ll touch on a couple of pre-production strategies, detail the sonic signatures of various acoustics, recommend a few top-selling EQ plug-ins and reveal proven, real-world EQ techniques for crafting stunning acoustic guitar tones.

Table of Contents

Evaluating the Acoustic Guitar Sound Before You Mix

Sound Profiles of Common Acoustic Guitar Bodies

Using Parametric EQ Plug-ins to Fine-Tune Acoustic Guitar Sounds

Working With Vintage EQ Plug-in Emulations

Six Proven EQ Tweaks for Acoustic Guitars

Fitting Everything Into a Mix

Why Some Effects Can Be Bad for Acoustic Guitar Mixes

The Awesome Acoustic Guitar Mix

Evaluating the Acoustic Guitar Sound Before You Mix

Mixing any instrument is a lot easier—and more productive—if the original source sound was superbly recorded in the first place. Unfortunately, whether you’re dealing with your own productions or taking on mixing gigs from others, you can’t depend on always getting well-recorded tracks. Sometimes, what you get is a distorted, howling mess that threatens to tank the entire song with its dreadful and appalling visage.

With acoustic guitar tracks, you may catch a break if the acoustic is not the main instrumental focus and is just there to provide texture or color. In these cases, the best decision may be to mute the track entirely and forget it ever existed. This is not a harsh, DEFCON 2 type of action—professional engineers and producers mute or move sections of tracks all the time to achieve the best possible mix.

However, if you’re dealing with a solo-acoustic performance, or if the guitar is the main engine of a singer-songwriter track, you’re going to have to dig in and make it sound as wonderful as you can. We’ll get to some potential EQ fixes later on in this article.

Obviously, you can’t do much of anything with tracks provided to you from an outside source. Most of the time, you’ll be stuck with what you get. (Welcome to the horrors of being expected to fix something you didn’t record yet are tasked with conjuring miracles to transform bat guano into gorgeous sound.) Although it can be a bit of an ego gut punch, it’s actually a fantastic stroke of luck if you are the rotten-recording culprit. Why? Because you can choose to put off the mix until you record a better acoustic track (or tracks). However, don’t make the same mistakes over again. Instead, dive into our tutorial How to Record Acoustic Guitar, and/or check out The Best Microphones for Recording Acoustic Guitar .

Pro tip: If you simply can’t bear re-recording an atrocious acoustic track, you can take an alternate action if the guitar was meant more as a percussive lift than a full-on “acoustic guitar part.” For example, sometimes producers use an acoustic guitar to fill the role of a hi-hat cymbal or shaker. If that’s the case for your less-than-lovely acoustic guitar track, then consider tucking in a shaker or maraca sample to evoke the desired rhythmic dynamics. You can even add a subtle delay to an existing electric guitar or keyboard track to percolate under the mix and produce much the same effect the acoustic guitar was meant to achieve. There is more than one way to invoke the dynamics of groove, so don’t stick with a poorly recorded track if other options exist. Power up your creativity and win the day.

Phase cancellation is another potential mix crusher when dealing with acoustic guitar tracks, as the original engineer may have used two or more microphones to capture a “widescreen” stereo image of the performance. Now, any time there are two audio paths for a single-source sound, it is extremely likely phase cancellation is present. In a typical case of recording an acoustic guitar in stereo, those two audio paths are probably one microphone positioned near the 12th fret (for mids and highs) and one mic placed around the bottom of the guitar body (for bass). The two mics may have invited phase cancellation into your mix, so listen critically to the acoustic tracks to ensure they sound sensational, rather than weak, anemic or flanged.

Of course, if phase cancellation exists, there’s always the chance that you like the effect, as it can thin out the overall acoustic tone. Perhaps you’re trying to seat the acoustic into a wailing sea of distorted electric guitars, and a slim and narrow tone with practically no bass content at all is absolutely the perfect fit. But if the acoustic guitar sounds strange or weird in a bad way, then fixing it before mixing it may save you the pain of doing a lot of likely unnecessary EQ tweaks at the mix session—especially if flipping a polarity switch on your mixer is all you need to do to make things right.

Get some knowledge on identifying phase cancellation, as well as tips on how to diminish it or eradicate it from our article What Causes Phase Cancellation and How To Fix It. The takeaway here is that even tiny improvements to your recording chops can save you from drama and tears at mixdown sessions.

Pro tip: Remember, an exceptional acoustic guitar sound starts at the source. Unfortunately, more than a few guitarists blow it before they even start recording by using a guitar with dead, beaten-to-hell strings. Encourage players to put new strings on their guitars the day before they enter the studio. You can also refer them to our excellent tutorial, How to Choose the Best Acoustic Guitar Strings. Beginning with a stellar acoustic guitar tone is more than half the battle of crafting an incredible sound for your mix.

Sound Profiles of Common Acoustic Guitar Bodies

Acoustic guitars come in several different sizes—from petite baby or parlor models up to the aptly named jumbo—and each one presents a rather distinct frequency range. Your EQ decisions will, of course, be somewhat informed by the type of acoustic used for the track you’re mixing. For example, you can crank the low-frequency EQ on a parlor guitar track if you want more bass, but if you’re trying to achieve the deep, resonant sound of a jumbo, the parlor’s tiny body simply doesn’t generate that much low end. If you persist, what you may end up doing is muddying the track by boosting flabby resonances (such as air booming within the body) or ambient and indistinct bass (due to signal bleed through the guitar mics if the guitarist was recorded live with a band). We’ll get to more specifics regarding EQ very soon, but let’s first take a peek at the tone profiles of some common acoustic guitar shapes.

Pictured: Martin D-28 Standard Dreadnought Acoustic Guitar

Parlor and Baby Acoustic Guitar Tones. Parlor guitars were actually made to be played in parlors way back in the 19th century, and they have enjoyed a resurgence in popularity due to celebrity performers, such as Ed Sheeran, Taylor Swift and Zac Brown. Small guitars have also become common in studio sessions because their focused and coherent midrange frequencies and lack of boomy bass make them great choices for fitting into dense mixes or adding acoustic textures under electric guitars, pianos or vocals. Similarly, solo acoustic performances with intricate picking sound clear and dynamically compelling on a midrange-forward parlor guitar.

The Grand Auditorium Guitar Sound. Grand Auditoriums are medium-sized models. Developed by Bob Taylor of Taylor Guitars in 1994, the shape was devised to accommodate both picking and strumming. The GA size is smaller than the popular dreadnought body and larger than a Grand Concert. You certainly get more low end than what is produced by a parlor guitar, and while the midrange presence is enhanced, the overall sound is relatively balanced between bass, mid and treble frequencies.

Tonal Character of Dreadnought Models. Likely the most popular acoustic-guitar size, dreadnoughts are renowned for deep, warm and boomy bass, as well as a slight dip in the mids that lets vocals really shine through. The top end is airy and clear. It’s no mystery why this shape and size is so prevalent, as it sounds great for flatpicking, strumming and fingerpicking.

Sonic Signature of Jumbo Acoustics. Jumbos are usually described as “strummer” guitars. They’re big—duh—so it takes a bit of an aggro attack to get the sound out of them. Not surprisingly, jumbo models generate a whole lotta low end, but their tight waist also produces a powerful midrange and a compelling high-end jangle.

Using Parametric EQ Plug-ins to Fine-Tune Acoustic Guitar Sounds

Remember that EQ superpower we mentioned at the beginning of this article? Parametric EQ plug-ins offer so many ways to fix, enhance or clarify frequency bands that they are like the audio equivalent of “Avengers assemble!” Simple EQ devices allow you to increase or diminish bass and treble—no big posse of superheroes there—but parametric EQ is absolutely crucial to the sounds crafted in recording studios because it delivers continuous control over numerous frequencies. You have full customization over the provided EQ filters, as each frequency band offers a choice of adjusting the center or cutoff frequency, the Q or bandwidth, boost or cut, or perhaps even more options (depending on the software).

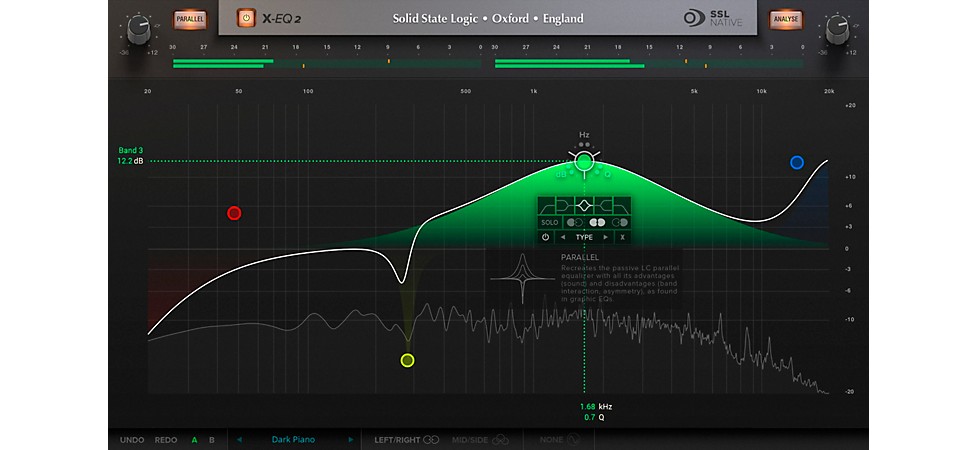

Pictured: Solid State Logic Software SSL Native X-EQ 2

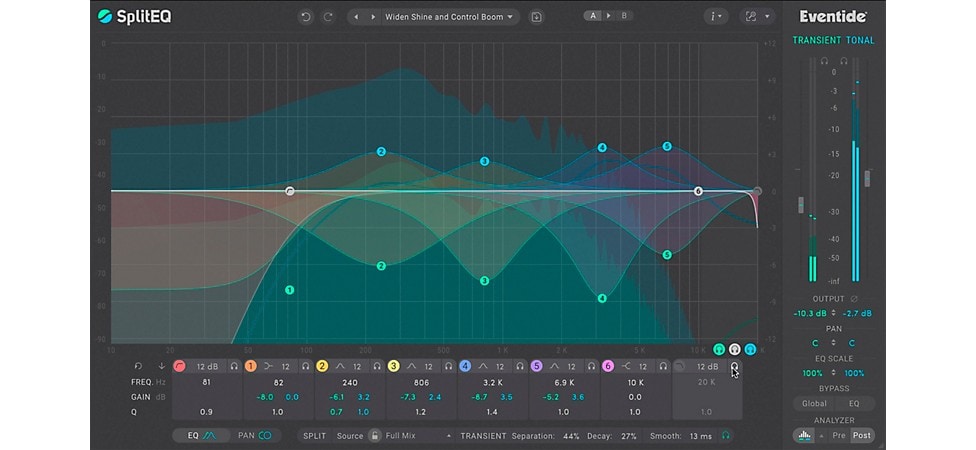

For mixing acoustic guitars of any size, having such incisive and specific control over annoying and energizing frequencies is powerful, and it can ensure your mix sounds amazing. For example, you can narrow the Q to target the precise frequency that needs attention, rather than boosting or cutting neighboring frequencies that may have nothing to do with the problem. Perhaps a picked note is a bit too prominent in an arpeggio, or it’s distracting to a vocal line. With a tool such as the high-powered Solid State Logic Software SSL native X-EQ 2 you can exterminate the offending frequency while leaving the rest of the guitar’s top end sounding bright and jangly. It’s almost as if what you did never happened and the spiky poke in the eye disappeared by magic, leaving the listener with a thing of beauty. If you don’t need quite the sound-shaping muscle of the X-EQ 2, two excellent—and less expensive—options are the Eventide SplitEQ Parametric EQ Plug-in and SONIBLE smart:EQ 3 Plug-in.

Pictured: Eventide SplitEQ Parametric EQ

Although it’s daring and fun to simply dive in and start attacking those frequency bands, take some time and familiarize yourself with the software. (Perhaps even—horrors—peruse the manual.) You might miss—or misuse—a valuable feature if you try to suss everything out on your own. These EQ plug-ins are formidable tonal assets. Know your tools.

Working With Vintage EQ Plug-in Emulations

Ultimate tonal supremacy is an incredible capability to have at your fingertips. While parametric EQs give you that kind of command, there are also vintage-flavored preamps and EQ plug-ins that exchange vibe for comprehensive frequency domination. These plug-ins are usually not clean or transparent. Instead, they impart all of the funk, color and beatific grit that analog mixers and processors of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s bestowed upon classic rock, jazz and pop recordings. Going vintage could be just the right sound for your acoustic guitar tracks as you seek optimum tonal impact for your mix. Pro tip: It’s a savvy studio strategy to populate your DAW with a parametric EQ for those times when you need precision and a vintage preamp/EQ for when atmosphere and character are more important than meticulous tweaks.

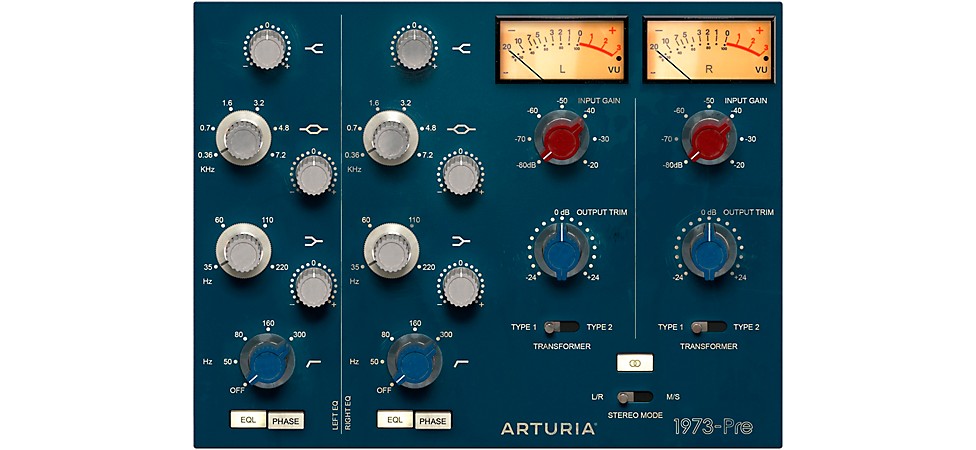

The Arturia 1973-Pre, for example, is modeled after studio legend Rupert Neve’s 1073 preamp/EQ—which is often referred to as the British preamp sound of the 1970s. The EQ section is quite straightforward—a high-pass filter (50Hz–300Hz), low-shelving EQ (35Hz–220Hz), mid-frequency EQ (±18dB at center frequencies from 360Hz–7.2kHz) and a high-shelving EQ (fixed at 12kHz—but it’s revered for its ability to craft musically pleasing sounds). Pro tip: When crafting an acoustic guitar sound, many pro engineers back in the day would set the 1073’s high-pass filter at 80Hz, cut at 100Hz or 220Hz (whatever worked best for the size of the guitar), boost 220Hz (if the guitar was a prominent part of the song), and boost the 12kHz high band to create airiness.

Pictured: Arturia 1973-Pre

One of the most magical EQs of all time is the Pultec EQP-1A Tube Program Equalizer, which appeared in 1961, and has been used on countless tracks since its release. (Motown used EQP-1As on just about every instrument and vocal, and the Power Station studio in New York City famously had two huge racks populated with 24 units.) Original, un-modded EQP-1As are rare and expensive, but you can experience much of the legend’s spectral glories with the Apogee FX Rack Pultec EQP-1A Program Equalizer. You can’t do surgical EQ with this EQP-1A emulation, but you can give an acoustic guitar track lush lows, steely mids and glistening highs. Furthermore, the hardware EQP-1A had a feature the manufacturer warned against trying. As the boost and attenuate controls each had dedicated knobs, you could simultaneously boost and cut a frequency. Fortunately, unruly and enterprising audio engineers disobeyed the recommendation and learned that boosting and cutting frequencies at the same time yielded very sweet EQ curves. The technical reality is likely due to the fact the boost knob has a higher gain than the attenuation control has cut, and each affect slightly different frequencies. But why even go there when you can instead treat your ears to some mysterious sonic sorcery. Pro tip: Engineers in the 1960s and ’70s discovered the EQP-1A enriched audio signals simply by running through the device with the EQ switched off. Try the same trick with the Apogee plug-in.

Pictured: Apogee FX Rack Pultec EQP-1A Program Equalizer

If you love the sound of the acoustic guitars on Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours album, the console that made that record was an API loaded with API 550A channel EQ modules. While a lot of the sparkle and awe was down to the brilliance of guitarist Lindsey Buckingham, album producers Ken Caillat and Richard Dashut were not shy about twisting knobs to get the sounds they were seeking. The Slate Digital FG-A Vintage EQ emulates the fully discrete circuit design of the API 550A, which has been sought after for its persistently musical sound since its debut in 1971. In fact, as much as the Neve 1073 preamp is celebrated as the “British sound,” the 550A can lay claim to representing the “American sound.” Pro tip: Start out with a 2dB boost at 200Hz to goose the low end of the acoustic guitar, boost 5kHz at 2dB to perk up the midrange, and then go for a 4dB boost at 10kHz to add high-end luster.

Pictured: Slate Digital FG-A Vintage EQ

Correcting an acoustic guitar that sounds too bright or too dull is one of the many skills wielded by the Soundtoys Sie-Q Equalizer Plug-in. Modeled after the Siemens W295b—a broadcast EQ developed by the German multinational company in the 1960s—the Sie-Q’s high end can be pulled back to smooth out an acoustic with too much bite or boosted to open up a sound that’s too dark. You can also deploy additive EQ without worrying too much about overdoing it, as the Sie-Q—like the original W295b—has sweet and silky EQ curves that can be boosted pretty aggressively before lows spew mud, or highs and mids get harsh. Pro tip: Don’t fear the treble. Cranking the Sie-Q’s high band is an excellent way to quickly add air, space and dimension to lifeless acoustic guitars.

Pictured: Soundtoys Sie-Q 5 Equalizer

Want to try something wild? Put a soul sheen on your acoustic guitar by using the Universal Audio Hitsville EQ Collection to simulate the jubilant, Motown Records R&B sound. The Hitsville plug-in is an accurate emulation of the original, custom-made 7-band EQ units that helped forge the Motown sound, and it offers two preset frequency bands that are perfect for creating airy acoustic tones: 5kHz and 12kHz. You can boost or cut each band by 8dB to find an epic, hitmaking acoustic guitar sound for your mix. After all, they didn’t call Motown’s Detroit studio “Hitsville U.S.A.” for no good reason.

Pictured: Universal Audio Hitsville EQ Collection

Six Proven EQ Tweaks for Acoustic Guitars

Well, to be more accurate, rather than “proven tweaks,” let’s call them “educated starting points,” as the size of the acoustic, how it was recorded and how the player approached their performance must be considered. For example, aggressive strumming produces more energy than subtle fingerpicking, so if you’re looking to cut lows, the specific frequency to address may be ever-so-slightly different than the EQ range we’ve selected. Trust your ears.

Lower the Boom. For an acoustic guitar in a dense mix, you can use a high-pass filter to eradicate all frequencies below 200Hz, as the instrument doesn’t “speak” much in that range. This will address any fears of muddy acoustic tones that can sully your mix. However, if you’re dealing with a sparse mix or a solo acoustic performance, you can leave much of the 20Hz to 200Hz range intact to add depth and resonance.

Body Work. The majority of a typical acoustic guitar’s fundamental tone and resonance reside in the 200Hz to 1kHz range. As a result, you may need to cut certain frequencies in this area that are creating flabby bass or muddiness. Take care not to cut too aggressively, as you might diminish the warm, natural character of the instrument. On the other hand, a small parlor guitar may need a boost around 100Hz or so to sound thick and weighty.

Get Clear. The 1kHz to 5kHz range is the sweet spot for an acoustic guitar’s clarity, presence, punch and jangle. If you’re dealing with an acoustic that sounds boring, dull and/or indistinct, look here to boost an area that brings the guitar back to life. Alternately, if the guitar is too bright, look for a frequency to cut that calms the bite. This is also the range where elements such as vocals, synths and electric guitars reside, so seek cuts that leave space for everyone else at the midrange party.

Shine On. The beautiful high-end shimmer of an acoustic is present in the 5kHz to 10kHz range. If you want more sparkle and air, look here. Keep in mind that it can be crowded up there, as cymbals, percussion instruments, screaming electric guitar solos and high-tuned snare drums can also inhabit the space. If your acoustic track doesn’t need stratospheric highs, consider using a low-pass filter to sweep out frequencies over 7kHz to make room for other glistening mix elements.

Two Ways to EQ. We all know musicians who feel that EQ exists solely to boost signals. Don’t be that person. You have two equally powerful options when addressing a frequency band—you can boost (additive EQ) or cut (subtractive EQ). Many times, savvy deployment of subtractive EQ will be the direction that makes the overall mix shine. Boosting every frequency in your path is a surefire way to summon those phasing problems we mentioned earlier in this article, as well as invite frequency glut, mud, shrillness and all of the sonic gremlins you don’t want in your mix.

Let It Be. Sometimes, the best approach for EQing an acoustic guitar is to do nothing. You always have the option of not touching the EQ controls at all—a decision quite a few musicians seem to neglect. True, if you’re dealing with a dense mix, the necessity of using EQ to get the acoustic to sit nicely within the soundstage is likely a done deal. But there’s no rule mandating that’s always the case. If the natural, unprocessed acoustic guitar sound carves itself out a masterful place in the frequency spectrum of your mix, just stop. Take the victory and move on.

Fitting Everything Into a Mix

Context is imperative when you’re trying to wrangle a clear, dimensional and powerful mix from a dense sonic stew of myriad elements. To ensure an acoustic guitar holds its ground in a track, you must establish which frequency ranges it may be colliding with or surrendering to. For example, an 88-key piano or keyboard can produce sounds across the entire 20Hz–20kHz bandwidth of normal human hearing. So, if the keyboardist is really pounding the keys high and low, there may not be a lot of room for the acoustic guitar to call its own. Your mission is to ensure the EQ profiles of each instrument stay out of each other’s way as much as possible.

There are many EQ charts available online (for free) that provide visual references of the frequency ranges of various instruments. These are decent aids for understanding the possible sound spectrum of a mix, but as acoustic guitars take up almost as much frequency space as pianos, they are definitely going to park themselves in the sonic landscapes of other elements, such as lead vocals, snare drums and electric bass. Critical listening comes to the rescue once again. First, zero in on sections that sound muddy, too bright or indistinct. For example, if you notice an annoying low-end bloom during a chorus, look for potential mud suspects—bass, piano, kick drum, etc.—and then check if the acoustic guitar’s low frequencies are also a sonic culprit. Eventually, you may have to choose “who” gets to strut their low end, and who needs to have their bass frequencies reduced. For quick guidelines on how to clean up the sludge, see our article 3 Savvy EQ Moves to Clean Up Muddy Mixes.

Pro tip: Don’t spend too much time dialing in your acoustic tone with the track soloed. Remember what we said about context? Unless you’re mixing a solo acoustic recording, the guitar will be heard by listeners within the context of the entire mix. If you don’t EQ the acoustic guitar while simultaneously listening to drums, vocals, bass, percussion and every other instrument, how will you find the sweet spot where it will sit perfectly amongst all of the other sounds? You won’t. Don’t mix in a vacuum. Listen to it all and EQ accordingly.

Why Some Effects Can Be Bad for Acoustic Guitar Mixes

We get it. Your creative muse is whispering in your ear to make the acoustic sound more unique, exciting or just plain bizarre. So, you open up your effects trick bag and start experimenting with reverb, overdrive, modulation and so on. No one should tell you that’s a bad idea. When conjuring great music, imagination, inspiration and ingenuity rule.

That said, whatever effect or effects you add to an organic acoustic guitar sound can complicate things—possibly inserting some frustrating corrective steps into your studio workflow. Depending on the resulting tone, you may need to do more EQ tweaks to get the acoustic to sit beautifully into your mix.

For example, let’s say you add a room reverb to the acoustic guitar. Ambient effects not only drop their own frequency emphasis into your source sound, they can also intensify finger squeaks and squeals. Maybe you want a chorus on the guitar. Well, the chorus effect might exaggerate cascading overtones. Compression can tame dynamics—making, for instance, fingerpicking runs sound more consistent from string to string—but it can also increase muddy bass frequencies produced by the guitar.

As always, the key to a successful mix is critical listening. If your effects choices sounded like good ideas in your head but end up befouling the clarify and impact of your mix, then you need to delete the effects or deal with the audio implications.

If you stick with the goop, you can diminish finger squeaks by zeroing in on the midrange frequency producing most of the screeching—perhaps anywhere from 1kHz to 3.5kHz—and cut it by 3dB or more. For guitar-body-generated bass boom, you may need to extend the high-pass filter to anything below 100Hz or 200Hz. To mitigate the overtones accentuated by a chorus, flange or phasing effect, you can cut some of the high or low frequencies obscuring the guitar’s fundamental frequency range, and/or reduce the wet/dry mix to favor the dry sound (the guitar).

The Awesome Acoustic Guitar Mix

Ultimately, you want your production concept to rule the mix at hand. If the acoustic guitar is the star of the show, then you should ensure its sound is seductive, spellbinding and absolutely gorgeous all on its own. However, if you’re layering guitar textures—whether those are a mix of acoustic and electric guitars, or an orchestra of shimmer under a lead vocal—you’ll need to use EQ to avoid any frequency ranges becoming oversaturated and muddy.

Pro tip: When you “finish” your mix, reference it to professional audio productions in the same general style—or to tracks that you love and admire for their sonic awesomeness—and determine if your work is comparable. If you notice sonic anomalies such as muddiness, frequency glut or overarching brightness, go back to your mix and address the issues. When your mix can hold its own against productions recorded in expensive studios with renowned engineers and producers, then celebrate. You’ve earned the indisputable title of mix master. Bravo!