When Gibson's then-parent company CMI launched its Maestro line of guitar pedals in 1962, not even its designers could foresee the massive influence on music it would go on to make. From the Fuzz-Tone FZ-M, based on the world’s first fuzz pedal in the FZ-1—as heard on the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”—to the all-new Ranger Overdrive, Invader Distortion, Comet Chorus and Discoverer Delay, the all-analog Maestro Original Collection blends Maestro’s signature space-age vibes with modern touches for a new generation of sonic sculptors. Its debut marks the iconic Maestro brand’s comeback after an extended hiatus.

We chatted with Mark Agnesi, director of brand experience at Gibson, to get the ins and outs of the new Maestro Original Collection family of pedals.

Tell us about your own personal relationship with Maestro.

Mark Agnesi: Well, like probably most guitar players, I didn’t know a whole lot about the brand. I knew the Fuzz-Tone, and I knew the Echoplex. It wasn't until a couple years ago, when we kind of got this project started, and then really in the last three or four months up here leading up to this launch, that I've taken the crazy deep dive into the brand and it’s rich, innovative history. When you look at some of the names that were involved and some of the firsts that Maestro delivered, it’s pretty incredible.

When we talked last year about the USA-made Epiphone Casinos, it was pretty clear what a huge Stones fan—Keith Richards, in particular—you are. Was “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” your first exposure to the Maestro brand?

That was. Obviously, I had heard that song, but I might not have found out that it was a Fuzz-Tone until after I was already hip to Echoplexes, that other great Maestro innovation. I think probably for the general guitar public, that’s really kind of the only big [Maestro] “moment” that's ever really been talked about. But there's so much more.

The Fuzz-Tone was originally a '62-ish release, right?

Originally, yeah. The Fuzz-Tone FZ-1 came out in 1962.

But “Satisfaction” doesn’t happen until a few years later, in 1965, which is when things really explode. What were the early years of Maestro like?

Maestro really gets its start in the early 1950s as an accordion company. Because it was owned by Chicago Musical Instruments, the same company that owned Gibson, Gibson started manufacturing accordion amplifiers in the mid-'50s, which were then branded and marketed under Maestro. In 1959, you see the invention of the Echoplex tape delay unit, as the accordion thing is kind of fading out at the same time. The Echoplex was first marketed under the Maestro brand in 1962.

In the early '60s, the Maestro brand name starts to get put on the Lyra Vibrola systems that you'll see on Gibson SGs and Firebirds. When the Fuzz-Tone came out in 1962 is really when guitar effects became a thing for Maestro. I don’t really know if the Echoplex was considered to be a delay “effect” when it came out. It was really more about being a sound-on-sound machine where you could do sound-on-sound stuff like Les Paul, the guitarist, was doing. I think it kind of got reimagined as more of a delay later on. So, really, '62 is when Maestro comes into its own as a pedal manufacturer with the Fuzz-Tone—the first fuzz pedal ever to hit the market.

Where did Maestro fit into the larger Gibson and Epiphone brands at the time? Were Maestro products being made in the same factories, side-by-side? Were they viewed as “complementary” products?

At that point, CMI was the parent company of all of these brands. A lot of these Maestro products were built at different factories by different manufacturers, at the same time sometimes. So, it really wasn’t like Maestro was Gibson’s brand at that time. They were both part of the same parent company, CMI. It’s not like we think of it today, where everything kind of falls under Gibson.

How’d the Fuzz-Tone come to be? It had its origins in a recording studio, right?

Yeah. The fuzz effect for guitar really was discovered by accident. Marty Robbins was in the studio, cutting a record. The guitarist, Grady Martin, had his guitar plugged directly into the console, but there was a bad preamp, and it was getting this dark, fuzzy sound. But, when everyone listened back, they kind of dug it. So, he cut the solo with that fuzzy sound.

Grady liked it so much that he later went back to the studio and plugged into the same broken channel to do his own instrumental song called “The Fuzz.” This recording then got The Ventures interested in it, which in turn got even more bands into it, until finally they decided to figure out what was going on and properly recreate the accident that was happening with that bad preamp. Glenn Snoddy, the engineer on the original Marty Robbins session, got to work designing a box that recreated the sound and, thus, the Fuzz-Tone pedal was born.

So, despite that early interest, the Fuzz-Tone didn’t sell well right out of the gate. Can you kind of speak to the before and after of the Fuzz-Tone taking off? “Satisfaction” hits in 1965, and that sound is just earth-shattering as a guitarist, right? It’s the sonic equivalent of the cultural impact of The Beatles going on Ed Sullivan.

Again, happy accident. The Fuzz-Tone was really being marketed as a brass instrument simulator. “Make your guitar sound like a brass instrument.” I think that was legend and hearsay of why Keith even used it. It was a rough track to try to simulate what he wanted the horn section on “Satisfaction” to sound like, and it ended up staying on the record. But the birth of rock-and-roll electric guitar sound, I mean, obviously, that is a huge moment in the history of guitar right there.

It's cool that the thing that started snowballing all the way back then really is how and why we ended up where we are now.

Yeah. A series of happy accidents, from discovery to misuse, created the sound.

When the Fuzz-Tone took off after “Satisfaction,” was there a noticeable difference in how CMI viewed Maestro?

Well, there was definitely an “aha” moment. The pedal had been out for three years, and it was selling, but it wasn't exactly on fire. All of a sudden, they were sold out, and I think the lightbulb went off that there was a market here for effects for guitar. And I don’t think it would've happened without “Satisfaction.” That was obviously what sparked the interest of players around the world. They realized that that they could make more sound with that pedal than just plugging their guitar into an amp.

And, of course, the Fuzz-Tone begets the Tone Bender. The Tone Bender begets the Fuzz Face. The Fuzz Face begets the Foxey Lady. The Foxey Lady begets the Big Muff …

And it still happens today when you look at the Klon and how many different pedals have been spawned out of chasing what the Klon does. There's always one or two that really break through, and then a lot of people start chasing, which sometimes is great because it leads to, like you said, the Fuzz Face. It led to the Big Muff. It led to a lot of these different things.

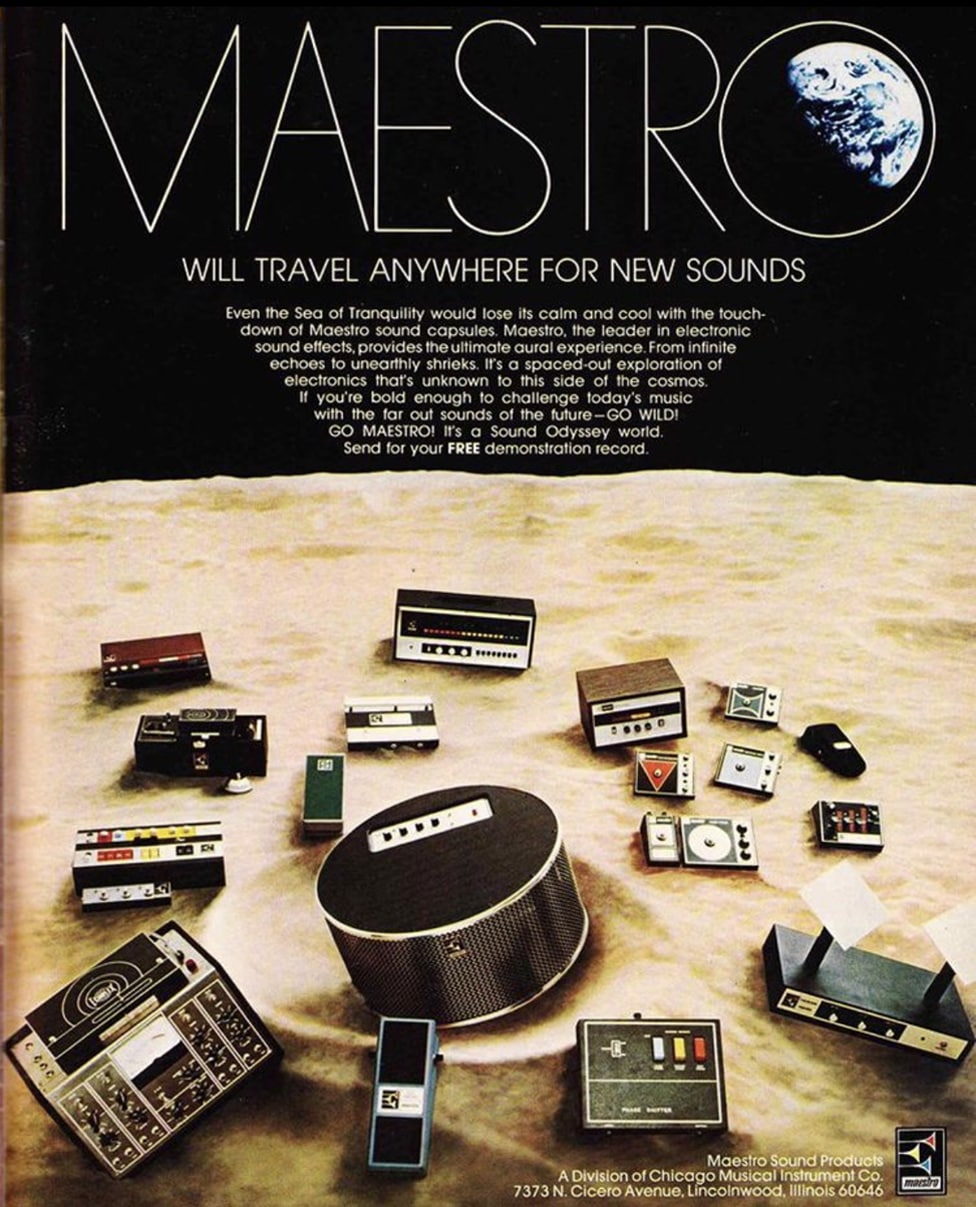

As you were relaunching the brand, going through all the old ads, can you speak to how the Maestro brand and the Fuzz-Tone were positioned? Was Maestro specifically advertising it like “as used by Keith Richards?”

Maybe not “as used by Keith,” but if you look at the old Maestro advertising, there is an outer space element to all of it. That “sounds from out of this world” kind of thing. And, really, for the time, it was because they were the first for so many of these effects that we all know and love now. Maestro was the first to market with quite a few of these designs. And I think that spirit of “shaping your sound” has always been there, and we're keeping that tradition alive and going.

Pictured: Maestro Ranger Overdrive, Maestro Fuzz-Tone FZ-M and Maestro Invader Distortion

If you fast-forward to the past couple of years, how do you see that brand heritage shaping what you're doing now?

Well, there's more to be revealed still. This is kind of the initial launch. What we have just released is what we're calling the Original Collection, which is in all the Gibson brand's portfolio now. For all of our brands, we’ve kind of rearranged product architecture to be an Original Collection, a Modern Collection and then this Custom Shop that does historic reissues.

So, what has just come out is our first offering, the Original Collection, and everything in that is true-analog, true-bypass, three-knob pedals. That's the Original Collection. Analog stuff. So, you can use your imagination and figure out where our brains are going for what the Modern Collection is going to be. And, obviously, a historic reissue collection at some point we would love to do as well, because there's so many of these classics that are really, really expensive now and very, very hard to find. To recreate some of these historic circuits would be pretty cool, too.

Can you walk us through the Original Collection a little bit? What would you personally use each pedal for?

Well, the Ranger Overdrive would be an “always-on” pedal for me. It's a great boost in front of an already overdriven amp, for leads and stuff, and it is a great choice for getting your overdrive sound with a cleaner amp—a solid all-around pedal.

The Fuzz-Tone … you know when you're going to use fuzz and when you're not, so that one's pretty easy.

The Invader Distortion is when you need to get nuts. There is a ton of gain in that pedal, but, luckily, you can harness it and control it a little bit using the switchable noise gate option that's on there.

The Comet Chorus is great if you need to get basic chorusing sounds, but it’s also great for the really, really weird, trippy analog chorusing and tremolo modulation sounds. It's all in there.

And the Discoverer Delay … anything from short slap backs to much longer, 600 ms-long delays. And, of course, you’ve got everything in between—all of the fun wackiness that you can do once you start turning the knobs to manipulate sounds. It's all in there.

It feels like you’re really taking care of the basics, getting the brand going again and telling the story.

I mean there are a couple generations of kids for whom Maestros never existed in their lifetime, and they might not know the story—let alone the history—and even people who know about it don't intimately know how influential and how big some of these innovations were. So, yes, first off, we have to start by bringing the brand back, putting it in the marketplace with some great effects that everybody uses. Let's make it analog. Let's make them true bypass, and let's reestablish the Maestro brand. And then where we go from here will be continuing to add to that, or add a Modern Collection, add a Historic Collection. This is going to be a slow burn that's going to arc over the course of the next probably four or five years, really, to have our whole vision come to life.

Will there be a Murphy Lab? [Laughs]

I don’t know if we're going to get the Murphy Lab involved. [Laughs]

Would you say the Original Collection is sort of the “Les Paul Standard,” in the sense that it fits within the ranges, going from Epiphone to a Gibson to a Custom Shop-type production?

Yeah. These would be your standard offerings. The Fuzz … obviously we have to do the Fuzz. It's Maestro. So, we’ve also got an overdrive, a distortion, a chorus that has some extra juice in there that does some really cool Maestro-y things, and then a great Bucket Brigade analog delay. These initial five are staples on everyone's board that we can get back in with. Then, as we continue to bring out new things, we'll start to hit some of those other things that people are wanting from us.

Pictured: Maestro Discoverer Delay

When you look at the pedals, there's a clear aesthetic to them, right? Obviously, it's that classic Maestro logo, but there's this kind of space-age, explorer vibe.

That has always been the look, even the vintage ones. Maestro has always had a cool look. We kind of focused and honed in on that wedge shape of the original Fuzz-Tone, and used that as kind of the blueprint for the Original Collection.

So, all the pedals have that same clamshell wedge shape. And the bugles light up, which is rad. In terms of aesthetic, even all the names are kind of NASA, space age-sounding names which we have a history with as well. As I mentioned earlier, if you look at all the old Maestro ads, the pedals were always on the surface of the moon. It was meant to be “out there.”

The original Fuzz-Tone is very gated, and starved for voltage, running at super low power. I noticed when playing the new model, when you play staccato, it certainly invokes that vibe of the Fuzz-Tone. But if you don't play staccato, it has a ton of sustain and seems to be a little bit more modern take on that. Can you touch on how the new Fuzz-Tone connects to the original? How did you reinterpret it for the modern guitarist?

One of the things we did with the new Fuzz-Tone that is a little bit different is that we made it silicon, whereas the original FZ-1 and FZ-1A are germanium designs. The pedal has two different voicings on it, a classic and a modern. So, when you're in the classic setting, we did try to voice it to get that nasally old-school FZ-1 sound. When you go into the modern mode, it's really a much more full-range-sounding fuzz and is capable of far more grit.

Of course, this kind of leaves the door open to do a proper historic reissue germanium FZ-1 or FZ-1A clone.

Was there any specific inspiration for the sound of the modern mode?

I wouldn’t equate it to anything else. I think it was just trying to make a sound that we think people would want to use. Obviously, people who hear “Fuzz-Tone” want that classic sound, so we had to incorporate that in there, but we really wanted to add a truly different voice that was big and wooly, and capable of doing what you would want a modern Fuzz to do.

Pictured: Maestro Invader Distortion

Listening to your demos for the Invader Distortion, it sounds great on guitar and bass. Is there any sort of shared DNA between the Invader and something like the Brassmaster, which was famously used by Yes bassist Chris Squire?

Not particularly. That pedal has got a dangerous amount of gain in it. It's not for the faint of heart, which is why it has that switchable noise gate on there. There’s actually a trim pot inside that you can dial in the threshold of where you want that noise gate to kick in. Depending on how loud you're playing, you might really need to get in there and tweak that threshold, because sometimes it will—I mean it's a serious gain—cut you off at certain volumes, high or low. So, you might have to go in there and tweak it.

We have fuzz and overdrive and a distortion in this initial five, and we really wanted to differentiate between the three. We wanted the distortion to be a full high-gain distortion pedal. The fact that it works killer on bass is a plus, but I don’t think it was necessarily designed with that intention, like the Brassmaster was. That was really designed to be a bass pedal.

You talked about how the Comet Chorus has some real “Maestro-isms.” And, when you switch into that Orbit mode, the waveform becomes really extreme. It's almost like having tremolo and chorus on at the same time, which is really cool. It's like one pedal for "How Soon is Now?" by The Smiths, or something like that.

So, outside of getting that traditional sound, how important was it for this pedal to have a switch to take things to a weird, far-out place?

It's Maestro, you know? Weird is in our DNA. So, any time that you want to go to that place, Orbit mode will take it there.

Again, there's a trimpot inside of that pedal which will specifically control the Orbit mode. It actually shifts full on, so that when people click it on, they actually understand what it does. You can dial that pulsing tremolo effect back with that trimpot, but it just adds a whole other dynamic layer and texture to what that pedal does.

Certainly, it’s something most chorus pedals don't do.

Not your regular off-the-wall, analog chorus is going to do.

Pictured: Maestro Comet Chorus

Anyone paying attention to your Instagram feed of late has seen your growing collection of vintage Maestro pedals. Have you been collecting with a specific goal in mind, or just grabbing stuff as you see it?

I have a cool job, right? With the Gibson Garage here and the Maestro launch, I have a big, historical display case in the center of the Garage. That display gets changed up with different exhibits that I curate. So, we decided that for the Maestro launch, I should curate an entire collection of original Maestro pedals to help tell the story for people who weren't fully aware of it, and then kind of showcase some of the crazy innovations that the company made.

So, in my personal collection, I've really been focusing on the Tom Oberheim era, which would be like that kind of late '68 to '73 era. I'm up to 12, and there are some that are becoming a pain in the butt for me to find, but there are still a few more that I want to get.

What's your favorite so far?

For me, so far, I think it's probably the PS-1, which is the Phase Shifter—which, again, was another one of the Maestro firsts. The first phase-shifting device. It's super unique, very, very warm. Ultimately, it was designed to try and simulate a Leslie, but what's really rad about it is when you switch between speeds, it actually ramps like a Leslie speaker would. So, you hear that ramp up and down. It's pretty amazing. Also, it's huge. They've seen pictures of them, but it’s the size of my laptop. It’s not pedalboard friendly, but it's sick.

Are there any real grail pieces, or sort of oddities or variants that you have been trying to track down that have been eluding you?

I don't know if it's super rare, but I'm just having a really hard time finding a bass Brassmaster. That's the one I really want to get my hands on that I don't have yet. And for the last three months, I've scoured everywhere and could not find them. I've got a couple that came from Japan. I've got one that came from Russia, and another from Canada. I'm scouring the globe trying to find these, and I still have yet to find a Brassmaster.

From this research and getting gear, are you finding you're really seeing the birth of a modern pedal line of sorts as you're going through that vintage stuff? Is there a through line you're seeing, the vintage gear you're trying to—or getting your hands on—where you can see that evolution that we kind of take for granted now?

I think we take it for granted now because there are so many options. But back then, all of this stuff came out of sheer creativity and desire to create new things and innovate things which is really amazing, and some of these, like the Filter Sample/Hold and the Envelope Modifier, are absolutely crazy. I mean even the Ring Modulator, too, which was late '60s. This is some pretty wacky sci-fi-sounding stuff that these guys were coming up with, and it's pretty amazing, but the idea of taking a guitar and making it sound like something completely different really seems to be the mindset that the company had back then.

Pictured: Vintage Maestro Ad

It's interesting when you consider that two of the biggest designers associated with it are these titans of the synth industry.

Absolutely. And that's something else I don’t think people really know about the history of Maestro. We had Tom Oberheim from ’68 until circa ’73. That same year Norlin, Gibson and Maestro's then-parent company, purchased Moog. Bob Moog and his team took over design and manufacturing in ’74. Talk about guys that can sound design! Those were the two chief creative guys behind what the company was putting out, and it's pretty amazing.

Looking back at all the Maestro gear that came out, what jumps out as the most impactful innovation? What has stood the test of time?

Innovations—there are a few. The real big “aha” moment after the Fuzz-Tone is Tom Oberheim joining the company. He had just developed the Ring Modulator. Maestro then began marketing the Ring Modulator, and then Tom comes on as the main designer, which is when things really start to go. That's when we get the PS-1 Phase Shifter.

There’s also the Boomerang Wah, which was already out before Tom joined, in 1967. There’s a very gray area as to whether VOX or Boomerang put out the first wah, but it was probably within a few months of each other. Maestro was also first to the market with the ME-1 Envelope Modifier, the first synth-based guitar product. The OB-1 Octave Box. The SS-1 Sustainer. These are all firsts for the industry. So, I really think when Tom Oberheim came into the mix as the designer, I think that's when the doors really blew off.

But I think post-Fuzz-Tone, the PS-1 Phase Shifter was really the next one that got major use by not only guitar players, but a lot of keyboard players as well. That became their new more portable option to lugging around a Leslie everywhere.

Pictured: Maestro Fuzz-Tone FZ-M and Maestro Ranger Overdrive

When you're digging into older designs, what do you think was the ethos behind these pedals? Do you get the sense that they were designed as, “How do we make the guitar sound different?” Were they purposeful innovation? Was it experimenting?

I think it's a little bit of both. I think some of them were absolutely driven by musicians.

For example, the Octave Box being able to bring your guitar one octave lower to mimic bass lines. That was obviously driven by guitarist demand.

The Sustainer, being able to hit a note and get infinite sustain on a note, was driven by feedback that they were getting from artists. Like, “This is something we would like to have.”

Then there's the really weird, wacky stuff: the FSH-1 Filter Sample/Hold, the Envelope Modifier, the Bass Brassmaster. Some of that stuff is just weird. It's weird. And being weird I think opened up those doors as well.

So, I think part of it was really trying to fulfill demands of current gigging musicians, and the other part of it was really trying to just break down doors on what the guitar could do sonically.

Is there any pedal in Maestro's history that you think gets written off as being too pedestrian, that's actually really cool? Or maybe something that's thought of as too weird, that you actually think is pretty usable, that people might not be aware of?

I don't know if there's really a sleeper, per se. There are definitely lesser-known ones, like the Filter Sample/Hold. When you're on the Hold side of that, it sounds like what people in the early 1970s would think a computer would sound like if it was talking. They nailed that sound.

The Ring Modulator is really cool and weird. It's an interesting, non-musical but mathematical circuit that produces some very odd-sounding things.

Can you tell the difference between the Bob Moog era versus the Oberheim era? Does the Maestro “voice” change?

The Fuzz is definitely changed up a little bit. It's really more about the design of the pedals.

The Oberheim-designed stuff is when you get those cool, bright color space age-y looking things. When you get into the Bob Moog era is when you see those big bricks with the rotary knobs on the side, that you can control with your foot. So, it was really the most noticeable thing between the two, the design aesthetics. Sound-wise, yeah, they vary a little bit, but it's not night and day. The Fuzz definitely changed up tonally during the Moog era. They stayed as weird as before with Bob there, too, obviously.

So, why bring Maestro back now? What was the thought?

This isn't the first time we've done this—look what we did with Kramer last year. Kramer was the number-one brand of guitars in the world in 1986 and 1987. Outsold Gibson. Outsold Fender. Outsold everybody. And then died and went dormant and needed to be brought back because it's an icon. It's an iconic brand, and that's what we resurrected. That seems to be our M.O. right now in resurrecting these iconic brands that had fallen out, and Maestro, in terms of pedals, is the most iconic and innovative, and frankly, the first to the party on so many of these things that we take for granted now. Now's the time.

What was your first reaction when you got your hands on the first new Maestro pedal?

Being totally honest, my first response was “Oh, my God, do those things light up when I step on it?” And I plugged it in, and the freaking bugles lit up! And it was awesome. So, before I even heard anything, if I'm being totally honest, that was my first reaction. It was like, “Okay, sick.” I mean I guess it would be different from one pedal to the other, but my first reaction was that they're very warm- and lush-sounding pedals. I always go after analog stuff, and just the warmth and tone of those pedals—I think pretty much right from the go, it was like, “This is where we want to be.”

Pictured: Maestro Comet Chorus and Maestro Discoverer Delay

So, let’s talk about the first time someone walks into their local Guitar Center and plugs into a Maestro pedal. What do you want them to experience?

The first thing I want them to experience is “fun.” It's fun, man. These things should be fun. They should incite creativity in you, and you should hear something in your head that you go, “I can do something with this.” I want musicians to feel creative and inspired when they plug into these. That's what I really hope that initial experience is.

And, not that beauty is more important than sound, but these are really beautiful pedals, too, and they're just beautiful to look at. They're going to look great on pedalboards when those bugles light up. Obviously, that’s secondary to the sound, but I hope people admire the design, too. We had a lot of fun coming up with what these pedals look like.

Aesthetic matters, whether it's conscious or not. The way a guitar looks and feels, the way an amp looks and feels—there's something to that, and if you're looking down at a pedalboard that's as visually inspiring as it is sonically, it's going to bring something else out in your playing.

I hope.

If you had to pick just one, which pedal is your favorite?

Hmm … it’s between the Comet Chorus and Discoverer Delay. The Discoverer Delay is probably my favorite. The Comet Chorus is definitely the coolest, though, I think. If you're looking for spacey, modular, cool stuff … I think that chorus, especially in Orbit mode, is going to blow some people's minds.