An unrepentant tinkerer, inventor and sonic explorer, the legend who was Les Paul dedicated himself to providing guitar players with a beautifully clean and expressive tone—even to the point of devising a low-output, low-impedance Recording model of his iconic Les Paul guitar. And that foundational sonic canvas left plenty of creative space for rock guitarists looking to spike their tone with an edge.

Those players wanted to unleash hellfire. They sought ragged, unique and ear-catching timbres—ferocious eruptions of frizzle, grit, grind, overdrive, unholy saturation and buzz. The sound of a new world shattering the old.

They wanted fuzz.

It’s a sound of fury and rebellion that got Link Wray’s “Rumble” banned from the radio in 1958, elevated the seductive sting riff of Keith Richards’ riff to “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” in 1965, and still powers the creativity of artists today.

One of the sovereigns of that sullied sound is the Electro-Harmonix Big Muff. It wasn’t the first commercially manufactured fuzz box, but it forged a gargantuan imprint on rock music, rock guitarists and iconoclasts of all styles.

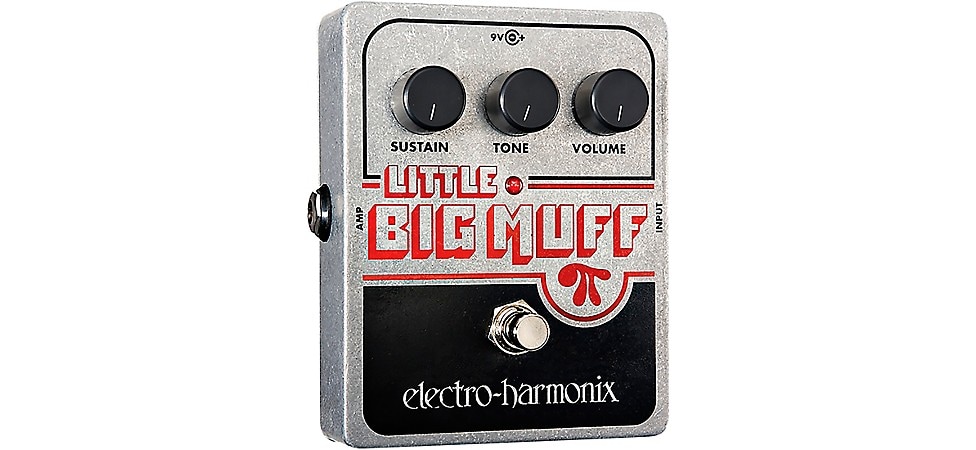

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Little Big Muff Pi

As Electro-Harmonix’s Alan Otto stated in Guitar Player magazine’s special fuzz issue in September 2011: “The fuzz pedal that started it all was the Maestro Fuzz-Tone. However, one of the most popular fuzz pedals ever made is the Big Muff Pi, which was introduced in 1969.”

In the divine paradise of guitar tone, EHX founder Mike Matthews is perhaps the dark angel to Les Paul’s cherub of clean. Matthews—an Ivy League electrical engineer who became a keyboard player, concert promoter and buddy of Jimi Hendrix—saw the future, and it was fuzz.

Matthews’ first product under the Electro-Harmonix banner was a guitar signal booster that viciously pummeled the front end of a tube amp to produce overdrive, and his second was the Big Muff. It was pretty much a home run, but like the fractured signal path that spawns fuzz, the trajectory of the Big Muff wasn’t exactly orderly or consistent. The pedal survived two bankruptcies of Electro-Harmonix, a discontinuation of the model, a move to Russia and subsequent manufacturing under the Sovtek name, a return to the Electro-Harmonix brand and American production, and a marvelous expansion of the line to meet the fuzz requirements of guitarists, bassists and producers.

This article celebrates the saga of the Big Muff and fuzz tone, divulges the Big Muff’s circuitry, details the artists that created blissful mayhem by plugging into a Big Muff and lists the many models of the current Big Muff “army” available today.

Table of Contents

A Quick History of Fuzz Guitar

Mike Matthews, Electro-Harmonix and the History of the Big Muff

The Circuitry of a Big Muff

The Difference Between Germanium and Silicon Transistors

Famous Big Muff Recordings and Notable Big Muff Players

A Guide to Today's Big Muff Models

Electro-Harmonix Triangle Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Classics USA Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Nano Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix XO Little Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Ram's Head Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix J Mascis Ram’s Head Big Muff Pi

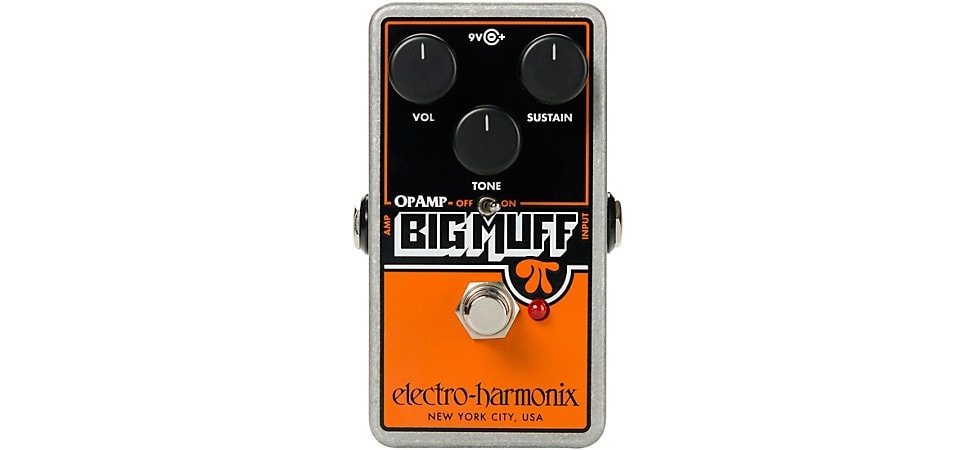

Electro-Harmonix Op-Amp Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Green Russian Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Sovtek Deluxe Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix XO Big Muff Pi with Tone Wicker

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi Hardware Plug-in

Electro-Harmonix Germanium 4 Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix XO Metal Muff with Top Boost

Electro-Harmonix Nano Metal Muff

Electro-Harmonix XO Bass Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Nano Bass Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Bass Big Muff Pi

Fuzz Out

A Quick History of Fuzz Guitar

Guitar lore is filled with tales of known and nameless early electric blues players who abused or maxed out their amps to create distorted tones. Some of those stories are true—even if the actual “Eureka” moments and their locations may be lost to history. But the earliest recorded examples of fuzzy guitar are similarly based in equipment failure or intentional mayhem.

The gritty stabs guitarist Willie Kizart dropped on Jackie Brentson’s recording of “Rocket 88” in 1951 were caused by a damaged speaker, after the amp fell from the roof rack of a car or was left outside in a downpour. The truth is out there somewhere. The root of the guitar overdrive in The Johnny Burnette Trio’s 1956 cover of “The Train Kept A-Rollin’” (written and recorded by R&B artist Tiny Bradshaw in 1951) is better documented. Trio guitarist Paul Burlison dropped his amp, causing one of the tubes to come loose. Burlison fixed the amp but was known to reach in and loosen the tube by hand whenever he wanted the sound of grit.

Rock ‘n’ roll renegades such as Link Wray (“Rumble,” 1958) and The Kinks’ Dave Davies (“You Really Got Me,” 1964) didn’t wait for happy accidents. They punched holes in their speakers to achieve distorted tones.

But the incident that may have inspired the actual manufacture of devices purely dedicated to creating fuzzy havoc did not involve a leather-jacketed rocker. The provocateurs were country artist Marty Robbins, Nashville session guitarist Grady Martin and a malfunctioning mixing board.

In 1960, while recording the song, “Don’t Worry,” the mixer circuitry hiccupped, turning Martin’s pristine, tic-tac-style 6-string baritone-guitar part into a blizzard of buzz. Martin hated it, but, fortunately for fuzz lovers everywhere, producer Don Law opted to keep the “mistake” in the mix. (Martin came around to the effect quickly, and even recorded a distortion-drenched song in 1961 entitled “The Fuzz.”)

A hit song—“Don’t Worry” owned the number-one position on the country charts for 10 weeks, and crossed over to reach number three on the pop charts—usually drives big or small changes in the creative and gear-manufacturing elements of the music business. While we’re not exaggerating the importance of “the fuzz mistake” on Robbins’ chart-topper, Gibson had its Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone on the market in 1962. It was the first commercially available fuzz pedal. America may have started the fuzzball rolling, but British companies really jumped in, producing classics such as Gary Hurst’s Tone Bender MK1 (1964), WEM Pep Box (1965), Arbiter Fuzz Face (1966), Selmer Buzz Tone and Marshall SupaFuzz (1968).

For insights on how the Tone Bender fuzz inspired Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Mick Ronson and scores of British and America guitarists, check out The History of the Tone Bender.

Mike Matthews, EHX and the History of the Big Muff

“Bigger than Life” is often overused when describing iconic individuals, but Electro-Harmonix founder Mike Matthews deserves the term, and his life story could inspire a pretty exciting Netflix limited series. We don’t have time for 10 episodes of classic Mike tales in this article, so for brevity’s sake we’ll just cover the hits. (But you should really treat yourself to “The EHX Story” on the company’s website.)

For a rock legend, it all started very Ivy League and corporate. Matthews earned a master’s degree in Electrical Engineering and an MBA in Business Management from Cornell University, and then worked at IBM. But seeing his first concert while at Cornell stirred an interest in music, and Matthews started playing electric piano and Hammond organ in a band, booking its gigs, and eventually expanding into promoting shows by The Isley Brothers, The Byrds, The Lovin’ Spoonful and others.

It was while booking a gig for Chuck Berry and opening act Curtis Knight and the Squires in 1965, that Matthews met Knight’s guitarist Jimmy James, forming a friendship with the man who would transform the guitar as Jimi Hendrix. With so much music swirling around him, Matthews wanted to quit IBM and play keyboards full time, so he was open to other business opportunities. One critical impetus came from Keith Richards’ fuzzed-out intro riff for the 1965 Rolling Stones smash hit, “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction).” Richards famously used a Maestro Fuzz-Tone for the sound, and Maestro couldn’t keep up with the crushing demand for fuzz pedals.

A repair tech in New York City suggested that he and Matthews partner up to make their own fuzz boxes, but Matthews ended up doing all of the work with another contractor. Around 1967, Guild Guitars ended up buying some of the models to market under the company’s name, dubbing them “Foxey Lady” pedals to capitalize on the popularity of Hendrix. For Matthews, the die was cast.

In 1968, Matthews—just 26 years old—founded the Electro-Harmonix company with his own investment of $1,000. The new enterprise’s first product—designed with help from Bell Labs’ Bob Myer—was the LPB-1 Linear Power Booster, which increased a guitar’s volume to the point where it battered an amp’s front end into producing a delightfully ragged overdrive. A year later, in 1969, the Big Muff Pi was born. In an interesting twist of fate, when Matthews visited Manny’s Music in New York to purchase some supplies, Henry Goldrich—the son of Manny’s founder—called out, “Hey, Mike. I sold one of those new Big Muffs to Jimi Hendrix.”

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi with Tone Wicker

Historical Note: There is some debate from Hendrix and gear fanatics over how often he used the Big Muff, as the guitarist is typically identified as using an Arbiter Fuzz Face during the Experience (1966–1969) and Band of Gypsys (1969–1970) eras. That said, there are photos from Hendrix recording sessions at the Record Plant New York in 1968 that show Matthews’ Guild-branded Foxey Lady pedal at the guitarist’s feet. In addition, Hendrix consistently experimented with sound and the available pedals of the day, and as he and Matthews were friends, it’s feasible Electro-Harmonix LPB-1s and early Big Muffs were made available to the legendary guitarist.

Of course, the story of Mike Matthews, EHX and the Big Muff is so extensive that Hendrix—as important as he is to rock guitar history—is just one chapter. The Big Muff sound did transform rock, and not just due to a single transcendent player, but because of a vast legion of magnificent guitarists and bands, including David Gilmour, J Mascis, Jack White, Ernie Isley, Carlos Santana, Billy Corgan, Ronnie Montrose, The Edge, Ace Frehley, Pete Townshend, Radiohead, Muse, R.E.M., Arctic Monkeys, Nirvana, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Sonic Youth, Kiss, Mudhoney and countless others.

There’s even more to the story. During the early 1980s, Matthews took on labor unions and the mafia to be able to produce EHX products in New York City. However, the dispute ultimately weakened the company and its finances, and Electro-Harmonix declared bankruptcy in 1982, and, again, in 1984. Saddened but undeterred (“It’s painful when you’ve built up something and all of a sudden, it’s gone,” he told Forbes), Matthews founded the New Sensor Corporation in 1988, and opened a tube factory in Russia—a move that revitalized the tube market. But pedals were apparently never far from his mind.

“In the early 1990s, I noticed all the Electro-Harmonix pedals I made in the 1970s were selling [used] at big markups,” said Matthews. “So, I started making pedals again. I gave the circuit diagram for the Big Muff and a sample to a small military factory in St. Petersburg, Russia, that was desperate for work. They laid out the circuit board, designed a new housing and made them for me.”

The Russian Big Muffs were released under the Sovtek brand in 1990, until Matthews brought pedal manufacturing back to the United States in 2001. He also committed his team to design and build new EHX designs. The Big Muff? It’s still rocking the world on untold numbers of pedalboards wielded by stars, aspiring stars and dreamers, and there’s a wide variety of Big Muffs available today—as you’ll see later in this article (or jump now to Today’s Big Muff Family of Fuzz).

By the way, in a near replay of the New York union debacle, the Russian sojourn eventually attracted mobsters and racketeers looking to force Matthews to sell his tube factories to them at far under-market prices. Again, he prevailed, retaining ownership of the New Sensor factories—although the current war between Russia and Ukraine, and the resulting export bans, began stifling tube supplies in 2022.

The Circuitry of a Big Muff

There’s a large community of boutique pedal designers who often refer to collections of online schematics to craft their personal takes on classic stompbox circuits. We’re not going to go as deep into the Big Muff Pi circuitry of 1969 as some of those schematic diagrams and explanations, but here is a broad stroke account of the Matthews/Myer design.

The seminal Big Muff Pi circuit was populated with common components that were easy to source—a boon for mass production—and the design was focused on stabilizing the behavior of its already pretty stable silicon transistors, as well as the pedal’s frequency response. The Big Muff Pi schematic was based somewhat on previous germanium-transistor designs—such as the Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face and Maestro Fuzz-Tone—and is separated into four distinct and simple blocks: Input Booster, Clipping Amplifier, Tone Stage and Output Booster. The clipping amplifier had two distortion stages, which were responsible for the Big Muff’s distinctive saturation and sustain.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix/SOVTEK Big Muff Pi

While Matthews may have been inspired by the busted-amp-like, over-the-top spittle of some ’60s fuzz boxes, the Big Muff Pi was conceived to be able to sound tight and focused, while simultaneously preserving the low-midrange chunk of the typical guitar tone. As a result, the Big Muff offered a versatile tone that worked great with chord progressions, single-note riffs and soaring lead guitar parts. You could also go into full sonic blitzkrieg mode if you so desired.

The Big Muff’s tone pot produces a high- and low-pass filter blend which gives the pedal its trademark scooped-mid sound. More specifically, when the Tone knob is set to its middle position, a notch at 1kHz is established. Depending on the model, some Big Muffs scoop out more mids than others, resulting in a darker, richer fuzz. If less midrange frequencies are scooped out, the fuzz effect is sharper and brighter.

That’s the basic, four-stage circuit of the Big Muff outlined in relatively simple terms. Homegrown pedal builders and the spec-obsessed who desire full cowabunga information on clipping cap, op amp and resistor values should check out circuit sites such as kitrae.net’s Big Muff Page.

The Difference Between Germanium and Silicon Transistors

Many of the early fuzz pedals were manufactured with germanium transistors, which is why, to this day, germanium-based fuzz boxes are typically considered as sounding “vintage.” For the Big Muff, Matthews decided to go with silicon transistors. Why? Here is a short tutorial on germanium and silicon transistors so you can see what factors may have informed Matthews’ choice of silicon for the Big Muff.

Germanium transistors debuted in 1948, but they were infamously unpredictable—mostly due to the difficulty of forming a stable oxide and a sensitivity to temperature fluctuations. In fact, extreme heat can cause a germanium transistor to fail outright.

Silicon transistors appeared in 1954—with Texas Instruments producing the first commercially available examples—and they were easier to make, more reliable and offered predictable performance. Silicon transistors were also less expensive than germanium.

Although perceptions of sound are subjective in the extreme, here are a few tonal characteristics of the two transistor types. It’s always going to be your call whether one or the other works best for your music. Silicon transistors produce up to 10 times the signal gain of germanium transistors, which typically delivers more saturation, more sustain, more high-end frequency content and a more raucous grind. Germanium transistors exhibit a slow signal-reaction time when compared to silicon transistors, which, in turn, produces a warm, smooth saturation with a bit of a low-frequency roll-off.

It's amusing, because while silicon transistors bring exceptional performance and quality for less outlay—a typical “win” for business entities and designers of solid-state gear—the drawbacks of germanium transistors (instability and unpredictability) are precisely the reasons some players dig that vintage germanium fuzz.

Famous Big Muff Recordings and Notable Big Muff Players

There are so many fabulous fuzz moments the Big Muff has brought to music and music culture, but perhaps the most surprising application of the Muff occurred on a track it probably had no business being a part of at all.

When The Carpenters were recording the syrupy ballad “Goodbye to Love” in 1972, Richard Carpenter urged session guitarist Tony Peluso—who had been playing a saccharine and silky solo that he thought was expected of him—to “Go! Just burn!”

Attempting to please the boss, Peluso plugged his Gibson ES-335 into a Big Muff and routed the pedal’s output directly to the mixing board. The result was a feral, barking rasp that was in direct conflict with the soft, easy-listening nature of the song. Carpenter loved it. “The way it growls at you is unbelievable,” he enthused to the song’s cowriter John Bettis.

Although it’s hilarious today to consider the public reaction in 1972, The Carpenters were denounced for “going hard rock” in reams of hate mail received by the band. But guess what? We can make the argument that the Big Muff—aided and abetted by Peluso and Carpenter—transformed “Goodbye to Love” into rock music’s first power ballad.

It wouldn’t be the last time the Big Muff informed a musical style.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix SOVTEK Big Muff Pi

Alternative rockers such as Dinosaur Jr.’s J Mascis, Mudhoney (who titled its 1988 debut EP, Superfuzz Bigmuff), Billy Corgan of Smashing Pumpkins, Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth, NOFX and Bush relied heavily on the Big Muff to create their odysseys of fuzz and distortion.

Fuzz fanatic Mascis collected an impressive number of ’70s Electro-Harmonix Big Muff pedals, which he evolved into a “Big Muff Museum”—complete with the appropriate shelving and place of honor—in his recording studio.

“My ultimate guitar sound was the first Stooges album,” he stated in the coffee table book, Stompbox. “That was the pinnacle to achieve—just fuzz and loud amps.”

Of course, as mentioned earlier in this article, the Big Muff is all over classic tracks by Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour (especially on Animals and The Wall), Carlos Santana, Thin Lizzy, Frank Zappa (who modified his pedal), Nine Inch Nails, Metallica, Depeche Mode (who titled its 1981 instrumental “Big Muff”), Ernie Isley (the compelling, near-psychedelic signal chain of a Fender Stratocaster, Fender Twin Reverb, Maestro phase shifter and Big Muff for 1973’s “That Lady, Pts. 1 & 2” by the Isley Brothers) and others.

If you’re into seeking out rarities, Scottish experimental artists Mogwai were honored with a custom Big Muff as a promotion for the band’s Rock Action album in 2001. Only 100 “Mogwai Big Muff” pedals were produced, and every one of them was allegedly given to music industry associates. (Nice perk, huh?)

A Guide to Today's Big Muff Models

Once upon a time, there was only the Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi. But then, variations appeared as the pedal evolved: Triangle, Ram’s Head, Black Russian, Green Russian and so on. Each version has its own fans, and most versions are still available today as reissues, limited editions or standard production models. Here are the Big Muff pedals you can plop onto your pedalboard today.

Electro-Harmonix Triangle Big Muff Pi

The EHX Triangle Big Muff Pi is an authentic re-creation of the company’s OG that blew the minds of fuzz-obsessed players everywhere. The Triangle version of the Big Muff Pi was identified by the pyramid arrangement of its Volume, Sustain and Tone knobs, and was produced from 1969–1973. This new version is housed in a more pedalboard-friendly chassis—and the “triangle” is now an inverted pyramid—but the circuit sounds like 1969, as if you just discovered the pedal at Manny’s on West 48th Street in New York City.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Triangle Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Classics USA Big Muff Pi

The EHX Classics USA Big Muff Pi brings back the sound of the “Ram’s Head” versions produced from 1973–1977. Also known as Big Muff Version 2, notable Ram’s Head users include David Gilmour (who rocked a 1974 version modified by Pete Cornish) and Ernie Isley.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Classics USA Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Nano Big Muff Pi

Get the classic ’70s Big Muff fuzz in a very tiny package with the EHX Nano Big Muff. A Nano is an excellent way to get some Big Muff vibe on your pedalboard—even if the real estate is already densely packed.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Nano Big Muff

Electro-Harmonix XO Little Big Muff Pi

The Little Big Muff Pi is a compact, road-toughened version of the classic ’70s fuzz box. The pedal is slimmed down from the 5.5" x 3" x 6.8" dimensions of the Classics USA Big Muff Pi to a more pedalboard-friendly 3.5" x 1-1/8" x 4.5". The chassis is also die-cast to better shrug off the abuse of multiple gigs.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix XO Little Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Ram's Head Big Muff Pi

There were three editions of the Big Muff Version 2. All have the art nouveau, Arnold Böcklin typeface (a fave of ’60s and ’70s art design) and the elfin, big-haired face in the bottom right corner of the pedal. Edition 1 has Big Muff and the Pi symbol in red. Edition 2 swaps the red for blue or purple. This was called the Violet Ram’s Head. For Edition 3, the color scheme returned to red, and the word “off” screened at the top middle of the box. The Ram’s Head Big Muff Pi is modeled after the 1973 Violet Ram’s Head model, which is considered to be the best sounding of the Version 2 models.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Ram's Head Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix J Mascis Ram’s Head Big Muff Pi

Packed into a space-saving nano-sized chassis, the EHX J Mascis Ram’s Head Big Muff Pi is based on the alt-rock guitarist’s #1 Big Muff from 1973. “That’s my sound—it’s always on,” says Mascis. “This Big Muff is the only one I use. The others are backups.” That’s quite an endorsement from a player who owns more than 50 vintage Big Muffs. Mascis voiced his signature model as close to his #1 as possible, with clarity and excellent string-to-string articulation mixed with a rich, aggro growl.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix J Mascis Ram’s Head Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Op-Amp Big Muff Pi

The Electro-Harmonix Op-Amp Big Muff Pi began its life as a strategy to match everything the silicon transistor Big Muffs could do, but with a simpler op-amp design that would cost less to produce. Howard Davis—EHX’s manager of analog circuit design from 1976–1981—was entrusted with the project by Matthews. Often identified as Big Muff Version 4, the distinct saturation character of the op-amps produced a scruffier tone that appealed to grunge and punk rock guitarists. Deploying three gain stages, rather than the four used by the transistor versions, Big Muff Version 4 pedals were described as having more crunch and edge, less gain and bottom end than V3 transistor versions and with the hint of a metallic chainsaw in its tonal textures. Billy Corgan was a convert, and he used the Op-Amp Big Muff on the Smashing Pumpkin’s 1993 album Siamese Dream.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Op-Amp Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Green Russian Big Muff Pi

The original Green Russian Big Muffs were manufactured in St. Petersburg, Russia, from 1994 until 2000 under the Sovtek name. These pedals were beloved by some guitarists and bassists because they produced relatively low gain, a stout low end and crystalline mids when compared to vintage USA Big Muffs. Interestingly, the enhanced bottom end is usually the reason why some players don’t appreciate the Sovtek Big Muffs. Much like the Ram’s Head Big Muffs by Electro-Harmonix, there were three editions of the Sovtek Green Russians, but the sounds of each version are pretty similar. For an example, listen to “Your Touch” by The Black Keys.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Green Russian Big Muff

Electro-Harmonix Sovtek Deluxe Big Muff Pi

The EHX Sovtek Deluxe Big Muff Pi is perfect for players who like some aspects of the Green Russian sound, but not others. The “Deluxe” element of this Green Russian—carried over from the Deluxe Big Muff Pi—provides enough tonal firepower to embrace and enhance the original Sovtek sound, or destroy it altogether and create your own sonic palette. The Sovtek Deluxe Big Muff provides a parametric midrange-EQ section (±10dB from 310Hz–5kHz), a Blend control for mixing dry and fuzz levels (perfect for bassists who wish to retain their instrument’s natural thump while adding a touch of gristle), and a Wicker for punching up the attack or preserving the conventional Sovtek Muff sound.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Sovtek Deluxe Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Big Muff Pi

The EHX Deluxe Big Muff Pi does about the same job for the tone of the American Big Muff as the Sovtek Deluxe Big Muff does for the Green Russian. Dig the basic sound of a traditional USA Muff, but some elements are a bit too thin and spiky for what you want to do? The Deluxe Big Muff’s fully parametric EQ section lets you punch up the attack or cut any problematic midrange frequencies, and you can also click the switchable Bass Boost to bring on more beef.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix XO Big Muff Pi with Tone Wicker

The EHX Big Muff Pi with Tone Wicker is another option for players who want to switch between the classic Muff sound and, well, something else. In this case, you get a trio of something else. There’s the traditional Muff sound with the Tone switch activated. Turn the Tone switch off, and the tone circuit is bypassed, producing a more transparent grind that lets the natural timbre of your guitar shine through—even at a dimed Sustain setting. With the Wicker switch on and the Tone off, you can evoke a vintage Rangemaster treble booster style of high-end bite—perfect for Rory Gallagher-esque snarling blues tones.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix XO Big Muff Pi With Tone Wicker

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi Hardware Plug-in

When is a plug-in not a plug-in? When it’s the EHX Big Muff Pi Hardware Plug-in. This is an analog hardware device that interfaces with your DAW to bring on vintage crunch from the source—not a digitally modeled version. The versatility of the Hardware Plug-in’s analog/digital hybrid is pretty astounding. You can use it as a traditional guitar pedal and bring the buzzy splendor of a 1973 Ram’s Head Big Muff to your live rig. Then, there’s the option of launching it as a plug-in within your DAW to process not only guitar parts, but also to saturate bass, drums, vocals, sitars, cajons and anything you desire with the Big Muff’s aggressive grind. But there’s more. Home-recording musicians can also deploy the Big Muff Pi Hardware Plug-in as a USB audio interface—just turn off the Big Muff effect for a robust yet clean input signal for your DAW.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi Hardware Plug-in

Electro-Harmonix Germanium 4 Big Muff Pi

The EHX Germanium 4 Big Muff Pi is like some sci-fi time machine that sends you back to 1969 to answer the burning question, “What if the Big Muff was designed with germanium instead of silicon transistors?” You can use the Germanium 4’s controls to emulate the sounds of classic ’60s overdrives or go for maximum sonic insanity via germanium-fueled fuzz and distortion. You can even starve the voltage feed to the germanium transistor with the Volts control to create brittle, dying battery timbres. While Big Muff disciples may argue you can’t really have a Big Muff if it isn’t built with silicon circuitry, the Germanium 4 offers a seductively extensive array of overdrive and distortion textures.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Germanium 4 Big Muff Pi

Electro-Harmonix XO Metal Muff with Top Boost

Here’s another one of those conceptual conundrums for you. Is it really a Big Muff if it’s a Metal Muff? Well, who cares? If you need a fabulously belligerent distortion for hard, in-your-face musical styles, the Metal Muff barks like a hailstorm of nails. If that’s still too tame, the Top Boost control can unleash even more savage sounds. Call it “Muff the Merciless.”

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix XO Metal Muff With Top Boost

Electro-Harmonix Nano Metal Muff

The EHX Nano Metal Muff is designed for fierce players who need hard-hitting distortion, but don’t have a lot of extra room on their pedalboards. The Nano Metal Muff is similar to the larger Metal Muff with Top Boost, except the Top Boost control is absent. You can still rage with intensity—thanks to the powerful Treble, Mid and Bass controls—and a bonus is that an onboard noise gate keeps the hum and audible hiss of extreme saturation at bay.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Nano Metal Muff

Electro-Harmonix XO Bass Big Muff Pi

In the competitive arena of “Why do guitarists have all the fun?” bassists have been plugging into overdrive and distortion pedals for years. Unfortunately, they’ve usually been “rewarded” with a buzzy tone that pretty much tanked the low end that made them bass players. (Revenge of the guitar players?) However, the EHX Bass Big Muff Pi bestows all of the crunchy wonder we’ve been discussing in this entire article to bassists without diminishing or stealing outright any of their bass frequencies. For Ireland’s classic rock-inspired Dea Matrona, guitarists-bassists Orlaith Forsythe and Mollie McGinn (who each switch between the two instruments) upend conventional bass tone and grooves by using a Bass Big Muff for inspiration. “It’s my favorite pedal ever,” says Forsythe.

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix XO Bass Big Muff PI

Electro-Harmonix Nano Bass Big Muff Pi

Bassists who want to mess with convention like the Dea Matrona duo, but who have small pedalboards, or simply want to carry their “secret weapon” in a coat pocket, can opt for the EHX Nano Bass Big Muff. The Nano offers the same low-end crunch as the Bass Big Muff Pi, but without the larger pedal’s bass boost switch. “I use the Nano Bass Big Muff to get the crunch in there,” says New York producer, bassist and DJ Blu DeTiger. “It’s my favorite distortion. It’s so sick.”

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Nano Bass Big Muff

Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Bass Big Muff Pi

The EHX Deluxe Bass Big Muff Pi—like the other “Deluxe” Big Muff pedals—offers enhanced tonal control, but, in this case, optimized for bass players. You can use the Deluxe Bass Big Muff with passive and active pickups, blend the dry and distorted signals to taste, output the effected and dry signals separately via dedicated jacks (as well as an XLR direct out) and activate a crossover that imposes a variable low-pass filter on the dry signal (for focused and coherent bass) and a variable high-pass filter on the distorted signal (to ensure the grit can cut through the mix).

Pictured: Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Bass Big Muff Pi

Fuzz Out

There are so many ways to summon Big Muff havoc that the options can be a bit, um, fuzzy. We’ve tried to help you find your favorite fuzz with this article, but as the Electro-Harmonix grind tribe is wide-ranging, we understand if you still have questions. Fortunately, our Gear Advisers have your back, so check in with a knowledgeable pro at your local Guitar Center store, or ring one of our call center associates at 866-498-7882.

You can also have a spot of productive fun searching for an EHX Big Muff in our Used and Vintage collection. A lot of models and editions are represented—even some authentic and well-cared-for vintage pedals from time to time—so you can be sure to find the perfect Big Muff buzz for your music. Time to put the pedal to the fizzle—or crunch, buzz, bark, grind, gristle, rumble, roar or psychedelic wail.